I’ve heard screenplays described as blueprints for homes that probably aren’t going to get built. Having written three, and after sitting through a dozen producer meetings that went nowhere, I get it. But I still dig the form, because TV and movies are collaborative in ways short story and novel writing are not. And some of what I write exists only in my head.

But sometimes it doesn’t.

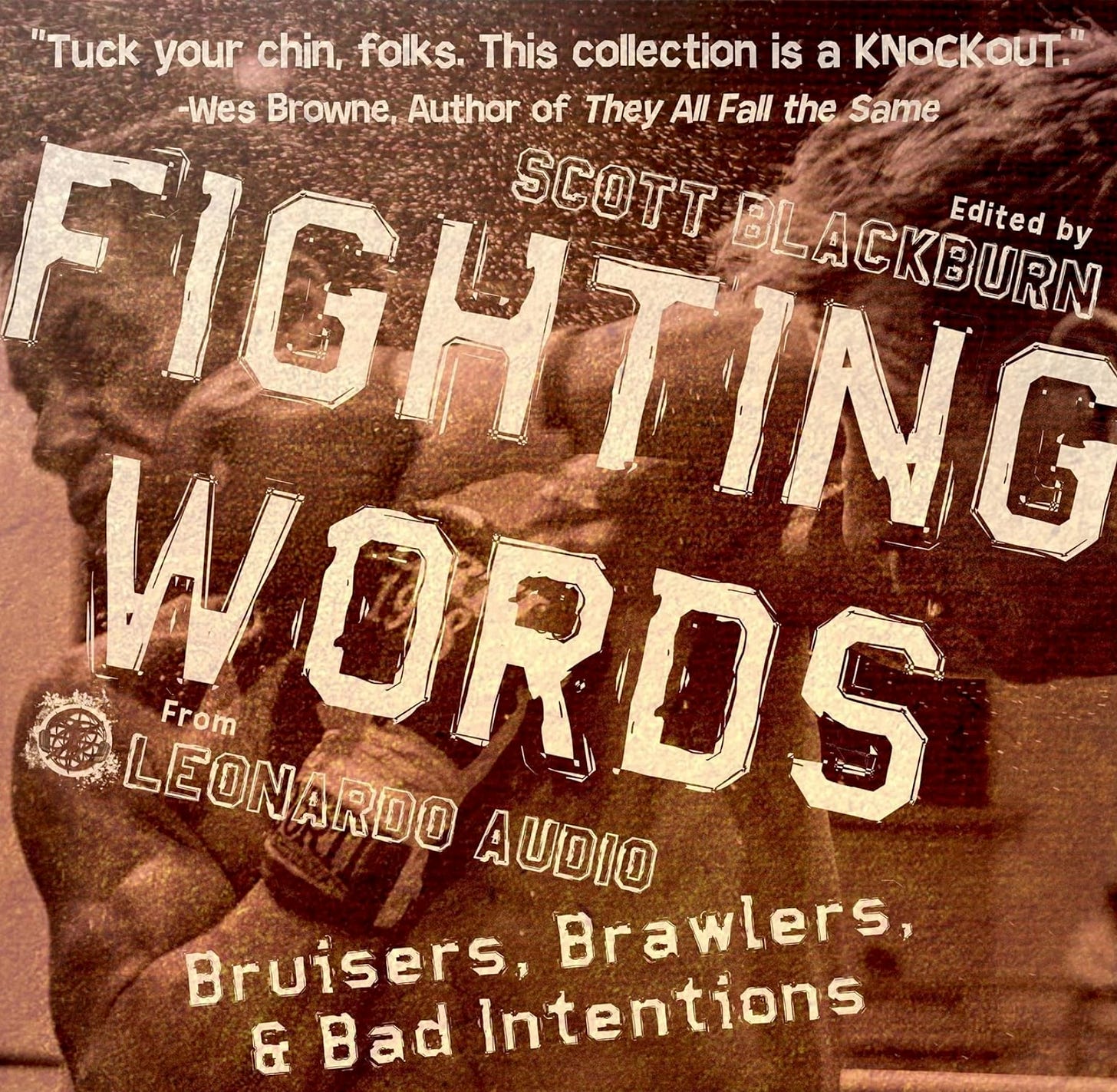

Early this year, Scott Blackburn invited me to contribute to a combat sports-themed anthology he was editing, entitled Fighting Words: Bruisers, Brawlers, and Bad Intentions. The real draw? This was an audio project. It’d be my first. I didn’t even have to think about it.

“I’m in,” I said.

“Great,” Scott said, before adding, “Hey, you know about fighting, right?” My former law enforcement career known among my writer friends.

Thing is, in twenty years with the NYPD, I threw maybe three punches. I don’t think any landed. I also maced myself once and broke an RMP chasing following an overly-enthusiastic street racer (the racer remains at large). My gifts, unsurprisingly, lay in talking defendants into surrendering and confessing and writing (very) long reports about both. Which wasn’t really this assignment.

“I live by my fists,” I said.

“Uh huh,” he said.

Scott’s dubious hesitancy making me a bit nervous, I pounded out The Cleaner, a story about an ex-con mopping up at an underground fight club. Scott chose it to close the collection, which includes new work by Nick Kolakowski, A.M. Adair, Meredith R. Lyons, and David Moloney, among others. In September, I got to hear my words read by Chris Ciulla, actor and professional audiobook narrator. A first for me. Which brings me to the nature of reading, audiobooks, and collaboration.

When it comes to fiction, I prefer ink and paper and silence. The world an author’s words create in my head is mine alone, and I cherish that ownership. In On Writing, Stephen King mentions how he only provides one or two physical details about a character’s appearance. King lets the reader create the rest. My Jack Torrance may look nothing like your Jack Torrance (Bad example—everyone’s Jack Torrance is Nicholson, right? But you get the idea). John Le Carré spoke of how the George Smiley in his head was eventually replaced by Sir Alec Guinness. This made writing the character harder, not easier; the moldable form in Le Carré’s mind now embodied by one of Britain’s greatest actors.

Similarly, every character I’ve ever written has had their own look, speech pattern, accent, style, and vibe. Those traits come out in the text—hopefully—but how do I know what I see as blue is the same as your blue? Audiobooks remove that uncertainty. When your words are read by a pro like Ciulla, they become concrete and uniform; the protagonist sounds the same to every listener. And good narrators distinguish every character. They enrich the experience. Chris Ciulla certainly did with The Cleaner.

I wrote a moment ago I prefer paper books, but there are two fiction series I’ve consumed almost entirely in audio formats. Both are set during the Napoleonic Wars, which probably confirms my middle-aged man status: Bernard Cornwell’s Richard Sharpe novels and Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey and Maturin books. Their respective narrators are familiar to me, I know what the characters will sound like. Even now, I can hear Frederick Davidson’s growling “Bastard!”, a phrase Richard Sharpe deploys often. But is the narrator’s “Bastard!” the same as the author’s?

There’s a character in audio version of The Cleaner who speaks with a southern American accent. I hadn’t written her thinking she’d been raised in the Carolinas or Georga. But Ciulla read the story and made a decision. His choice threw me at first, but I settled in and now I dig the added dimension. This is the beauty of collaboration; another creative taking a story element and building on it.

Is my blue the same as your blue? Take a listen and find out.

Fighting Words: Bruisers, Brawlers, and Bad Intentions is available now on Audible and as an ebook, from Leonardo Audio.