I love grim stories. For years I’ve been writing what’s referred to as “grit lit” or “neo-noir”. To paraphrase Tom Hardy’s Bane, I was born in the darkness. Emotionally gutting fiction—in novels, movies, or TV—generates deeper reactions in me than any other kind. They made me hurt. More than that, they make me feel.

Bleakness is having a moment. Every year, the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles hosts a week of films exploring humanity’s dark side. This year, that program expanded to seven other independent theaters nationwide, including my beloved Coolidge Theater outside Boston. I could not attend any screenings, but was there in spirit. I read my usual slate of crime novels about bad men doing terrible things and downed some truly dark cinema. Good times, yeah? You’d think, but there came a moment in the fourth episode of Justin Kurzel’s phenomenal Australian series The Narrow Road to the Deep North, where I wondered if even I, fanatical devotee to the religion of despair, had reached my limit.

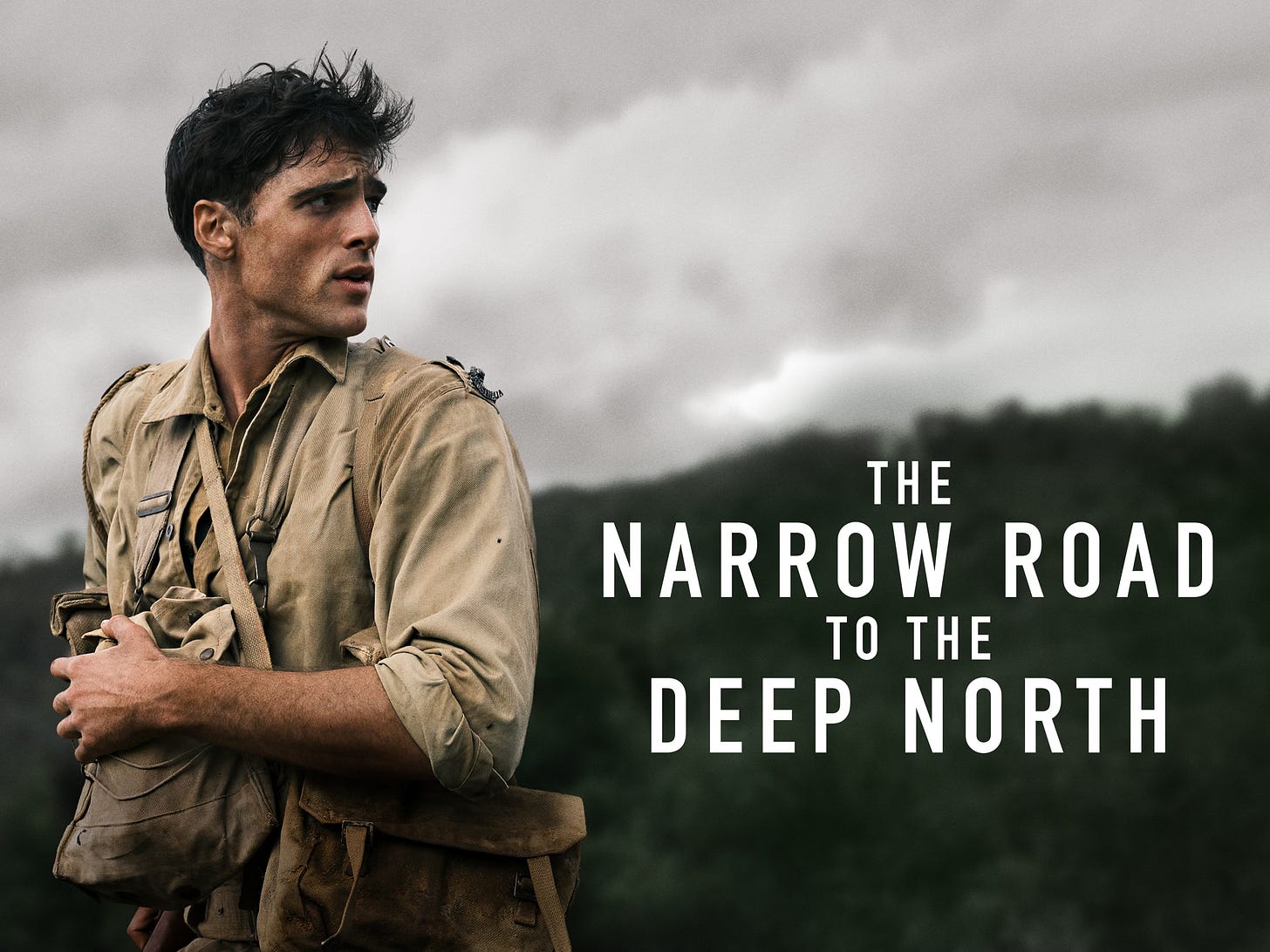

If you haven’t heard of this show, I don’t blame you. It’s logged under two-thousand ratings on IMDB and has received zero marketing in America. Adapted from Richard Flanagan’s 2013 novel, Narrow Road is a dual-timeline story about an Australian army doctor who loves two women and is captured by the Japanese in the early stages of World War II. Jacob Elordi, in a revelatory turn, plays young Dorrigo in sweaty, pained, emaciated, POW gauntness. Ciarán Hinds—The King Beyond The Wall!—is the older, accomplished man, now a respected-but-rash surgeon haunted by what he endured and visions of the soldiers he could not save. The series is lush and cinematic, and the plot unfolds slowly, with long stretches of measured silences that reminded me of Terrence Malick at his wheat-field, locust-swarm, navel-gazing best. Dorrigo faces unspeakable hardships as he cares for Aussie POWs forced by their Japanese captors (Tokyo Vice’s Shǒ Kasamatsu shines again) to build a railroad through the southeast Asian jungle. Men starve. Men are beaten. Humanity fades. Prisoners die quietly and sadly, their last breaths coming in weak exhalations. This is Bridge of the River Kwai for the sickos.

Narrow Road to the Deep North is an unexpected remnant of the streaming revolution’s great promise: well-funded prestige projects about real people mounted by visionary auteurs. It is glorious and haunting and got to me in ways I had not expected. The final episode left me in stunned, contemplative silence. It is, without exaggeration, a modern masterpiece.

I also cannot recommend it to anyone but the hardest of the hardcore.

While darkness in cinema has its audience, publishing seems averse to it right now. I’ve written previously about the industry’s current desire for escapism, at least in the crime and thriller genres. I’ve also written about how disappointing I find this. Crime novels have, historically, provided platforms from which writers explore class, corruption, racism, sexism, institutional brutality, and rampant hypocrisy. That’s the pool I swim in. My second novel’s out with editors now. It is not a warm blanket beach read. More like a shiv to your kidney as you’re staggering back to your feet after getting fishhooked by a scarred felon in a sketchy bar. It is the literary representation of my cop-affected worldview. Narrow Road drew me in not in spite of its inherent darkness, but because of it.

And then I came to episode four.

Oof.

Some of you might remember 2004’s The Passion of the Christ, Mel Gibson’s (I know, I know) vision of Jesus’s final hours. That movie basically showed Jim Caveziel (I know, I know) getting brutalized for 127 minutes. And it made $610,000,000 worldwide (I miss movies’ cultural centrality). But I don’t know anyone who’s fired Passion up for a rewatch. It’s just too much.

Narrow Road’s fourth episode focuses on Thomas Weatherall’s “Darky” Gardiner, one of the weakest prisoners under Dorrigo’s care. I won’t spoil the details, but Kurzel’s depiction of Darky’s fate made me—a man who’s watched all thirteen hours of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Too Old To Die Young three times!—hit pause and take a walk. It’s an hour of unflinching honesty; Imperial Japan’s martial fervor produced well-documented atrocities. When a young female reporter questions 1980s-Dorrigo about the allies bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki, an offended, dismissive Dorrigo asks if her studies have gifted her perspective. His sentiment being, if you weren’t there, you can’t understand. That, for me, is the draw of dark stories. To force the otherwise comfortable into confronting uncomfortable emotional truths.

A few weeks ago, I started drafting a new novel. I don’t outline or sketch. I dive in, and let the characters dictate the story. This one has surprised me. It’s darkly comic and features endearing characters a reader might even describe as—sigh—likable. I have, to this point, avoided writing premise-driven, commercially-appealing books. I have also, to this point, failed to sell a novel, my agent instead receiving complimentary passes from editors praising my writing while also pointing out how small the audience for such work is. We all know the definition of insanity. So, the new project.

Call me pretentious, but I have always dreamed of writing an “important” novel. A book that speaks to timeless themes and is well-reviewed by critics and thought highly of by other writers and gets considered for literary awards. I’m cringing writing that, but it’s true. Money has never been a motivation for me. I’ve always sought emotional validation in my work, whether that’s been homicide investigations or publishing. And the quickest route to cultural relevance, I’ve long thought, were “serious” novels. I’ve since learned that’s either not what the market wants, or, frankly, that my writing’s not good enough. My reach might very well exceed my grasp.

And now my allegiance to The Bleak seems to be fracturing. Either I’ve awakened to the realities of publishing as a business, or I’ve gone as far down this narrow road (see what I did there?) as I can. Maybe a lighter tone will shove a marketable book out of my head. Maybe I shouldn’t be against writing pure entertainment. Maybe I should pivot to servicing readers, instead of only myself. Then again, any creative’s got to stay true to their vision. I expect this novel will, at times, darken. There will be violence. But it won’t follow Jacob Elordi into that jungle and watch his mates die slow.

As for Narrow Road to the Deep North, it remains an impressive achievement that deserves to be watched. But, for God’s sake, please don’t binge it.

You watched Too Old to Die Young three times? You're a crazy person. (I only watched it one and a half times. I don't think you and I have ever talked about Too Old to Die Young before. I am not surprised that we're among the 25 people who love it, though.)

Great post, Jason! I like my stories dark as well, will have to check out this series.