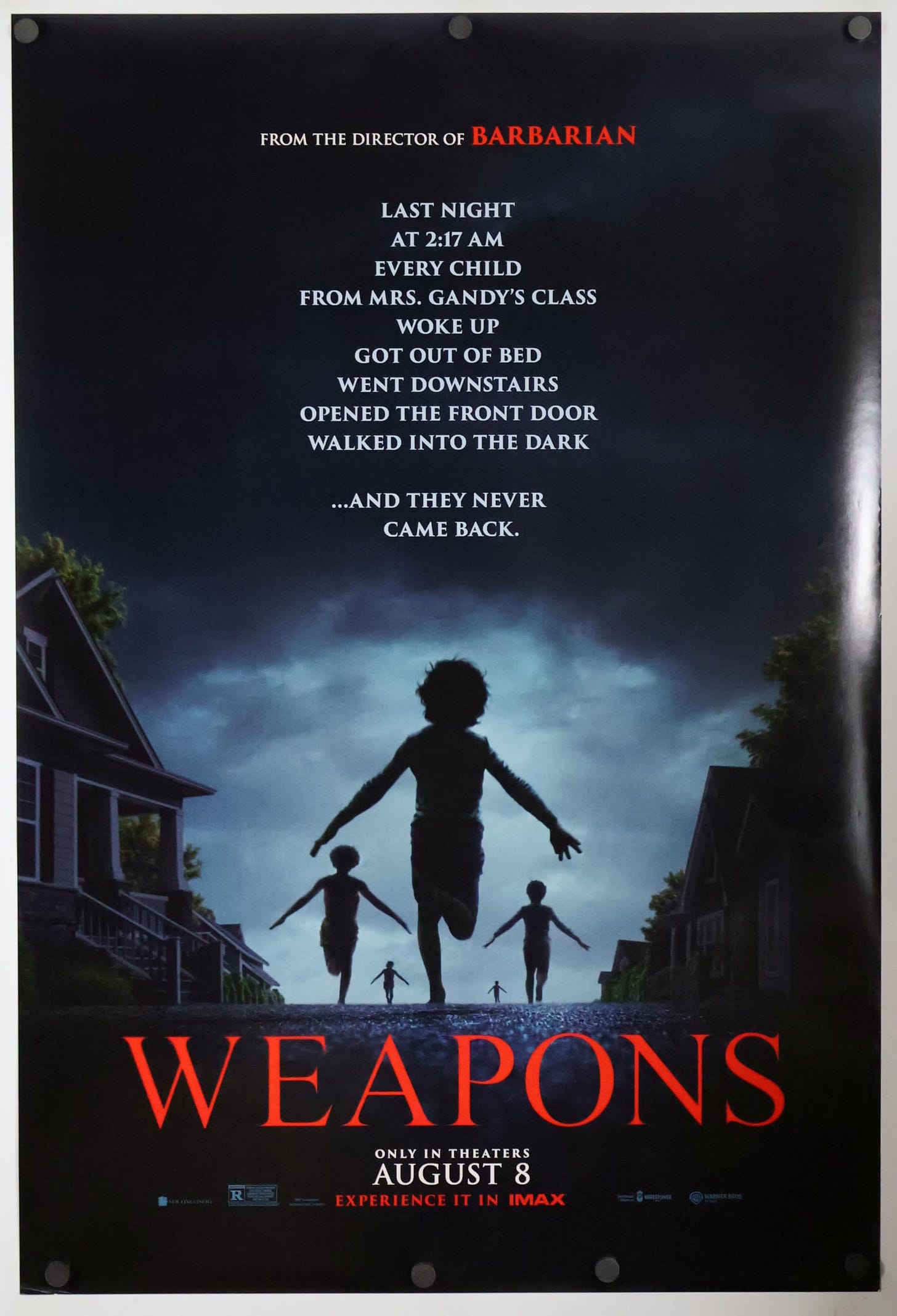

The Weapons teaser had me hyped. Pixelated footage of grade school kids running down darkened suburban streets with their arms locked out is undeniably creepy. I respect but didn’t love director Zach Cregger’s first feature, Barbarian; the guy’s got style. Then the full trailer dropped, and my interest wavered some. Still, the movie’s a phenomenom and I’ve got Regal Unlimited, right? Last Monday night I settled into a pretty crowded 9:30 showing.

And I walked out sadly underwhelmed.

Don’t get me wrong, the movie has some eerie moments and disturbing imagery. It’s well-staged and shot. But it also promises more than it can deliver. That’s not entirely Cregger’s fault; horror almost always fails to payoff intriguing setups. It’s a bug in the system. And few creatives have figured out effective solutions. David Lynch sits at the top of that list.

Maybe my mistake was seeing Weapons the day after finishing my Complete Twin Peaks Rewatch ‘25 World Tour. And by “world”, I mean my sofa. On which I sat through two seasons of the original series, the Criterion edition of Fire Walk With Me, and all eighteen parks of The Return. If I had any doubts that Lynch (and Frost’s) twenty-seven-year project is my favorite piece of American popular culture, this viewing erased them. Twin Peaks is a miracle. If fire engulfed my house, and I could either rescue my wife and dog or my TP bluray boxed set, there’d be a moment of indecision. A brief moment, but still.

Like I said, horror resolutions tend to underwhelm. It’s hard to payoff mysterious setups in credible ways. I’m still scarred by ABC’s 1990 adaptation of Stephen King’s It (spoiler: the adult versions of the kids Pennywise tortured beat a giant bug to death. Which was Pennywise’s true form. I think. It was a long time ago, okay? Also, I don’t know what happened in the novel—I never read it).

Here’s Weapons’ premise: one night, at the exact same time, every child in the same grade school class—except one—left their homes, ran into the night, and were never seen again. Cool, right? The problem started for me when the first post-setup scene is prefaced with a title card reading JUSTINE. Uh oh, multiple POV chapters incoming! And that’s exactly what Cregger lays on viewers; six segments focusing on different characters navigating the aftermath of the kids’ disappearance. Every eight to twelve minutes, the perspective shifts and the narrative starts back at one. The story circle keeps spiraling outward, to characters less invested in the tragedy, before (finally) coming back to the missing kids. But Cregger has given us the answer long before that point. All we can do is watch how he gets there.

Unlike Kurosawa’s Rashomon and PTA’s Magnolia, which weave plot threads and shift perspective in a way that builds tension, Weapons felt like a car that kept stalling out. I was into Julia Fox’s alcoholic, troubled teacher, forced to deal with a horde of angry, grieving parents. Give me her story. Wait. Who’s this heroin addict? Why are we in his makeshift campsite? The school Principal’s grocery shopping? There’s no time to get invested in any character because Cregger keeps whip-panning to another. And the explanation, when it comes, feels small while also devolving into an over-the-top gorefest played for laughs.

The writers Anton Chekov and Michael Haneke are credited with expressing the notion that great art asks questions, it doesn’t answer them. David Lynch understood that better than anyone. He famously never discussed his movies, television shows, art projects, their themes or his intentions. That unyielding refusal to provide easy answers made him a hero of mine. Then again, except for Peaks’ insanely popular first season, no David Lynch project could be labeled a commercial success. Weapons, meanwhile, has pulled in $200 million worldwide as of this writing. Maybe I’m the weirdo?

Twin Peaks: The Return is a masterclass in not giving into nostalgia and pat resolutions. Viewers eager to watch Agent Dale Cooper drink coffee had to wait SIXTEEN HOURS to see Kyle MacLachlan in the role that has defined him. Along the way, Lynch and Frost gave us Mr. C/Bad Coop, the Black Lodge entity that inhabited Cooper in the legendary second season cliffhanger; Dougie Jones, the childlike Las Vegas insurance agent in which Cooper is trapped for most of the series; and Richard, the alternate-timeline (maybe?) version of Cooper that shoots cowboy dipshits and ignores obvious homicides. Lynch will not service fans cheaply. Part 17 manages to expand brilliantly on events depicted in Fire Walk With Me, satirize comic book culture’s lazy, fist-meet-face (or floating head) climaxes, and tease something approaching an explanation.

Then Part 18 hits, and Lynch kicks us right in the cherry pies. The Return’s finale undoes all that came before, dooming Laura Palmer and Dale Cooper to playing variations of the eternal victim and failed savior across infinite timelines.

I remember watching the finale when it aired on Showtime, frantically checking my watch as Dale Cooper/Richard and Laura Palmer/Carrie Page drove across an endless night, bound for Twin Peaks. Fifteen minutes left, then ten. “They’re not going to make it!” I remember thinking. And they don’t, because in the story we’ve swerved into, Laura Palmer never lived in her childhood home. But evil entities from Fire Walk With Me have. A bewildered Dale Cooper/Richard asks “What year is this?”, Sarah Palmer’s haunting voice calls out, “Laaaauuuuurraaaaaa…” and Sheryl Lee unleashes a horrific scream and the the lights in the Palmer house cut out and the screen goes black. Cue credit roll over a slow-mo shot of Laura whispering to a terrified Dale Cooper in the White Lodge. She’s given him the answer, but Lynch keeps it from us. It is frustrating and maddening. But here I am, writing a newsletter on a TV series eight years after it ended.

Because I can’t stop thinking about it. Because Lynch knew the power of mystery. Because he wasn’t afraid to challenge viewers. Because the world is an inherently confusing place onto which we try to impose structure. There’s a saying in writing, how non-fiction doesn’t have to make sense, but in fiction every piece needs to fit. If those pieces involve Amy Madigan wrapping hair around twigs and snapping them, no thanks. I’m good.

I had the exact same experience watching the Return finale, looking at the clock and realizing answers were not forthcoming. I am embarrassed to admit I was disappointed at the time, to the extent that I didn’t like it. But now, of course, I think it’s brilliant, and can hear Laura’s scream and its metallic echo in my head eight years later without even having watched it since then. Who needs an explanation when that’s the effect of the enigma?

Totally agree with your takeaway about Weapons, the setup was a thousand times more interesting than the payoff. You're also spot-on about the general problem with horror mysteries, where the question is generally more intriguing and interesting than the answer.